drag·o·man (dr g

g

-m

-m n)

n)

n. pl. drag·o·mans or drag·o·men

An interpreter or guide

The attorneys are yelling at each other, eyes bulging, and then one of them is yelling at me.

“Mr. Joe,” the lawyer says, screaming. “You do not ask the questions, here. We do. So stop asking. Just listen. And then answer.”

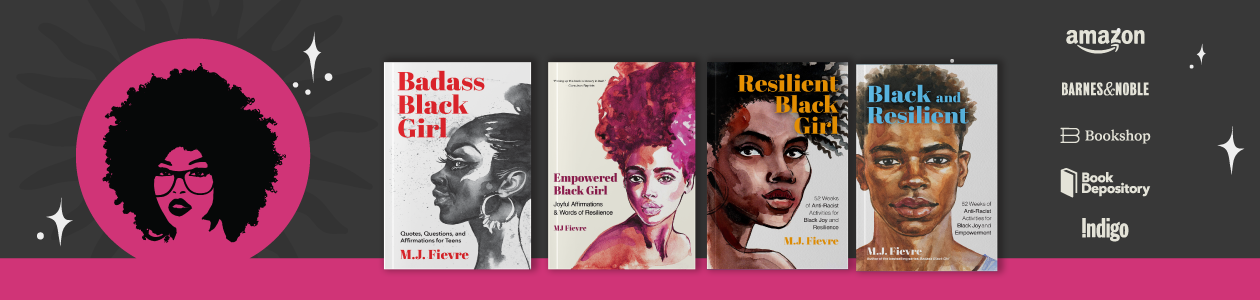

I’m not Mr. Joe. In fact, I’m not a man at all. See for yourself:

(Yes, this is me, in an unprofessional Selfie. In the car, I’m always eager to lose the suit.)

I’m only the (Haitian-Creole) interpreter. And yet this man is looking at me, yelling at me. All the while addressing me as Mr. Joe.

He’s angry at Mr. Joe, not at me. I know that. But my body doesn’t. My muscles tense, as something rises in me, from my stomach to my throat. Bile. My heart taps, then races. I don’t deal too well with aggression. I often portray myself as having thick skin, but all it takes to intimidate me, apparently, is two men with sharp suits and perfect haircuts, raising their voices, looking me in the eye.

Mr. Joe is staring at me. The attorneys are staring at me.

I can’t help but to feel small, although I’m doing a grand job, translating as well as possible. The court reporter is keeping her cool. She’s pretty and tiny. It is 2013 and we are all obsessed with thinness. We were all trying desperately to disappear.

I’m good at this, I remind myself.

“But I don’t understand,” offers Mr. Joe, his voice trembling.

“I don’t understand,” I translate, my own voice rendered frail by intimidation.

Being an interpreter requires controlling your emotions. Sometimes, during a deposition like this one, lawyers will forget you’re only the bridge; they will direct their frustration at you.

When I first started interpreting, I was in college. I met with Charlie, my contractor, at a restaurant on A1A.

“Oh, my,” he said, “You’re young.” He was in his sixties, soft spoken. “Are you sure you can do this?” he asked. “Sometimes the clients get really—colorful.”

“Sure,” I say.

A week later, I was cursing in an insurance office.

I went to Catholic school all my life—from the first grade to my last year at Barry University, in Miami Shores. So I was impressed by my own arsenal of curse words in Haitian-Creole. As the f bombs flew and the b-words clashed into each other in spicy sentences, I translated.

“You’re such a c*nt!” the witness said. “I want the insurance to pay for the f*cking surgery.”

My heart was in my throat, my stomach in my heart. His wife was screaming, choking sobs exploding from a dry throat.

I closed my eyes and translated.

I later apologized to the insurance lawyer for calling her a b*tch.

“I’m used to this,” she said. “They come here—and curse. Not your fault.”

She clicked away, hands in pockets. Turned back at the last moment to wink. At the vending machine, she laughed while she plunked her change for a candy bar.

I opened my cell phone to let Charlie know about my first job. Intake air, then breathe out.

The person you’re interpreting for can also see you as the enemy. My friend Andres was once interpreting for a Puerto-Rican drug dealer. Years later, he met the thug at a gas station in Hialeah.

“I remember you,” the man said. “I’m going to kill you. Te voy a matar.”

I found a solution to this misdirection: I’ve stopped offering eye contact. When things get heated, I look at the walls. I memorize the door jam, watch the ceiling. Somewhere, outside of me, voices elevate as they ask questions. I translate without looking at anyone.I also wear my poker face.

When they can’t catch my eyes, they direct their attention toward the real target of their anger. I look at my fingernail polish. It is perfectly applied, without bubbles.

(Oh, and if you need an interpreter in the Dade/Broward/West Palm Beach tri-county area, email me at fievrerouge@gmail.com)